Everything You Need to Know About Film Grain and Pixelation

![]()

When you take an analog medium and make it digital, there are bound to be questions. Especially when turning that digital image into a print on photo paper, photographers aren't always sure if what they are seeing is film grain or pixelation.

So, how do you control film grain and pixelation in an image? And how can you tell the difference between them?

WHAT IS FILM GRAIN?

Film grain is the visible silver crystals in a film negative's emulsion. These light-sensitive silver halides change into pure metallic silver when exposed to light, which is how an image is captured on film. So, grain is an inherent part of a film image.

The higher a film stock's ISO is, the bigger the silver crystals are. That means a higher speed film will have more visible grain, while a slower speed film will have a finer grain.

Black and white films like Ilford Delta 3200 and Kodak TMAX P3200 all have more noticeable grain. And so do color negative films like Kodak Portra 800.

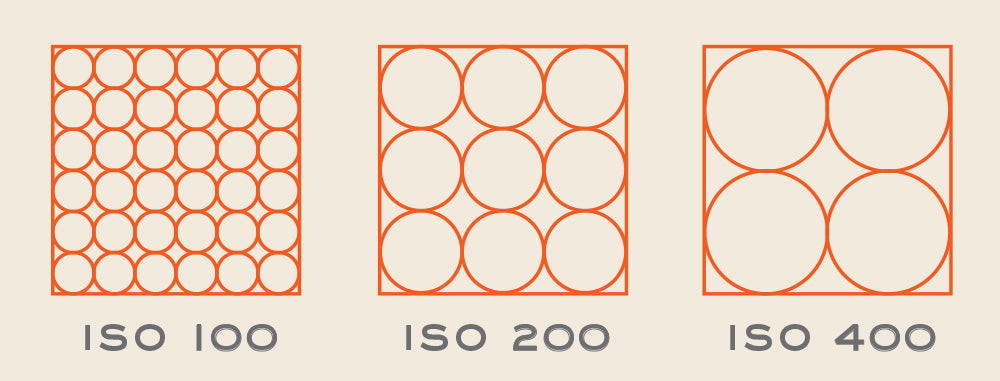

The below illustration shows the approximate grain-size difference in three different speeds of film.

However, it's important to note that the above illustrations aren't exactly what a roll of film's grain structure really looks like.

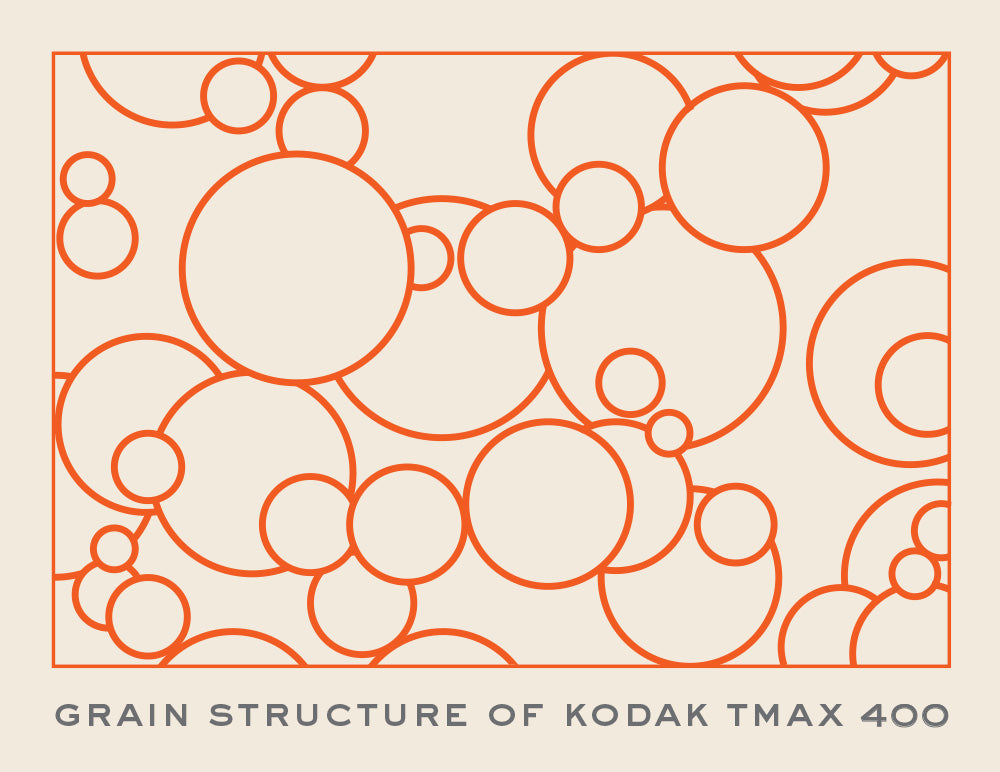

First, the silver crystals aren't perfectly and uniformly distributed in a grid pattern. Second, while each film speed has a size of crystals that is most common in its emulsion (the sizes in the image above), all film stocks have many different sizes of crystals in them. That's what allows them to capture a range of lights and darks.

Below is an example of what a silver-crystal structure actually looks like in a film stock.

What exactly magnifies the appearance of grain besides the speed of your film? Primarily it’s your exposure.

Underexposing your film will increase the amount of noticeable grain on any film stock, especially in the shadows of the image. That's because very little light hit the light-sensitive silver crystals, so the smaller unexposed crystals wash off the film in processing while the bigger crystals remain.

If you dramatically overexpose your film, you will also start seeing more grain in the highlights and midtones of your image.

Film developing for longer than normal (aka pushing your film in processing) will also create more noticeable grain. Another thing that will make grain more apparent: enlarging your negative! The more you zoom in, the more texture made of tiny crystals you'll see.

It's important to note that none of these things are physically adding grain to your film. Instead, they are making the grain that is already there more pronounced.

WHAT IS PIXELATION?

Why does pixelation become part of the film grain conversation? Because sometimes photographers aren’t sure if they are seeing grain in the image or pixelation, especially in photo printing.

Pixelation is an effect of low resolution. Resolution is the amount of detail an image holds. When an image holds less detail than the output on which it is being displayed, you can see the individual units of color/value (aka pixels in a digital image) that make up an image. That's when pixelation occurs.

Conversely, the higher the amount of pixels in an image, the clearer an image will be.

Pixelation is easiest to understand visually:

So what does it mean for an image to be "low resolution"? There is no precise definition across the board. This is because how an image is being displayed, and at what size, determines what resolution is required for it to look crisp and clear.

Many people think that DPI (dots per inch) is the end-all be-all of resolution. But, the true key to judging resolution is the pixel dimensions of an image, and putting that in the context of how an image is being displayed. There's two ways to break down why this is...

First, DPI is only half the story when it comes to resolution. The other half is the actual length/width of an image. DPI x length/width = pixel dimensions.

For example, these are the measurements for a photo that is 6 inches wide at 300 Pixels Per Inch (PPI):

6 inches x 300 pixels = 1800 pixels

That 6 inch image above has the same number of pixels as a photo that is 25 inches wide at 72 PPI:

25 inches x 72 pixels = 1800 pixels

The second thing that tells us DPI doesn't determine resolution is the method by which an image is displayed. Simply put, an image being displayed on a screen needs fewer pixels to display clearly at a specified length/width than an image in print. The pixel dimensions that are required are different depending on the final output.

Learn more about the nitty gritty of resolution, especially as it relates to printing, here.

You may have noticed that Richard Photo Lab delivers our scans at 300 DPI—but that doesn't mean they are pixelated! Medium and large scans are delivered with high enough pixel dimensions for printing high quality images (at differing sizes, of course). So if you're seeing something "funky" in your film photos or scans, it's probably related to grain!

HOW CAN I TELL IF IT'S GRAIN OR PIXELATION?

Especially when looking at a print, sometimes photographers aren't sure if what they are seeing is film grain or pixelation. That's because prints are where resolution problems become most prevalent. But there are two easy elements that will tell you if your print is grainy or pixelated...

The first element is structure. The architecture of grain is different from pixelation. Grain causes random noise across an image, but it doesn't really change the clarity or level of detail in an image.

Pixelation, however, can appear more grid-like (think 8-bit video games from the 1980s). Especially on the edges of items in the image. The less pixels there are, the more evident this structure becomes. Pixelation also causes loss of detail.

![]()

The second element is value/contrast. The texture that film grain adds to an image is seen because of the added contrast (range of lights and darks) that the crystals provide.

In an image that is pixelated, the contrast does not change from that of its high-resolution counterpart.

In fact, there is actually a smaller quantity of tonal values being displayed than a high-resolution image, because there are less units of color/value (pixels) that are making up the image.

The moral of the story? In film photography All film has some level of grain, but not all images are pixelated.

And now, you can tell which is which!

Start Your Film Order